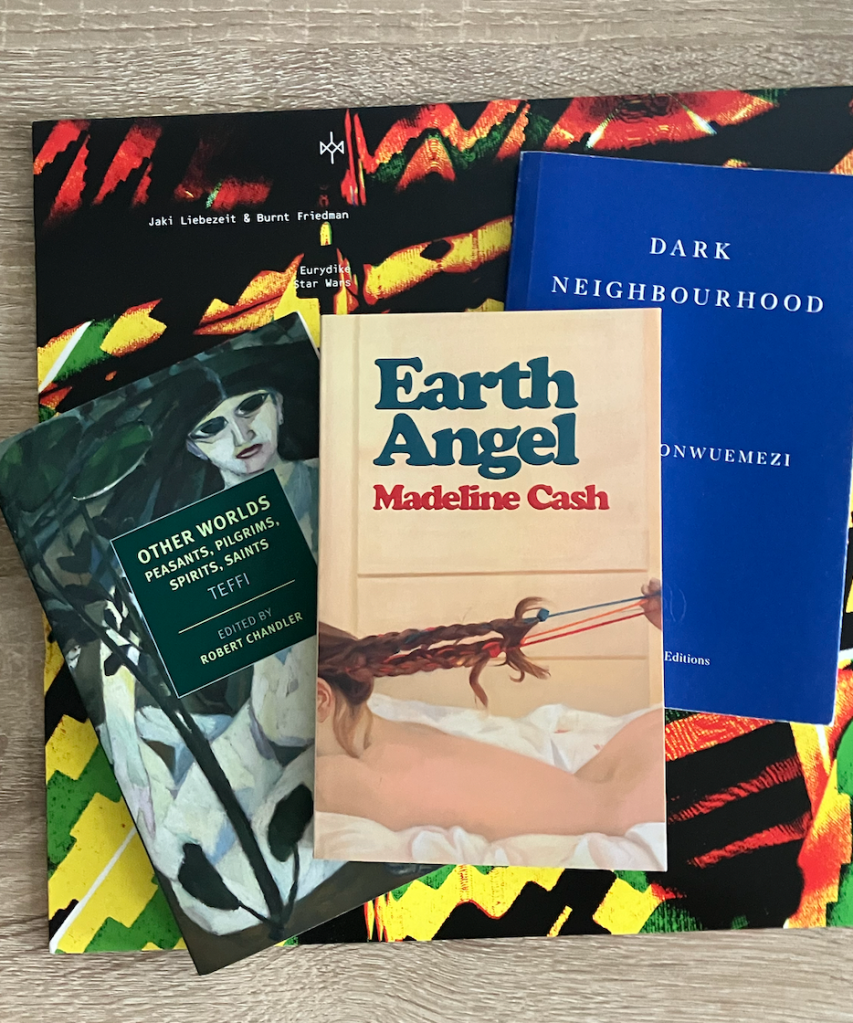

In Madeline Cash’s “Plagues,” God punishes 21st century Southern California with frogs and drone strikes raining down from the sky, Brita filters that turn water into blood, and cows suffering from yeast infections. But these plagues, as horrible as they are, make everyone happy, because each is proof that God is real and has returned to His creation.

Post-pandemic, the worst part of getting sick is the barrage of questions. After my fever last weekend, everyone I know reached out to ask if I had a headache (yes, a small one), a sore throat (yes, it was horrible), or lost my sense of taste (no, I spent Sunday ordering $50 chicken sandwiches from Uber Eats). Friends became plague doctors, checking off symptoms to determine the route of my disease vector. It was annoying.

In Vanessa Onwuemezi’s “At the Heart of Things,” a woman falls down a subway escalator and hits her head. It doesn’t seem too bad, she gets back up and goes to work, but that night she falls into a deep dream. Water pressure holds her; she floats senselessly. Over the next few days, she rotates between therapy, the library, phone calls with friends, and dropping back into her unconscious ocean, where the only presence is that of her friends, not felt or heard but there among the eels, tubeworms, and brine.

The deep sea’s senselessness floods her waking life. She floats toward an edge beyond which she can see nothing. Saying goodbye to her loved ones, she sinks into the abyss.

The best part of getting sick is the fever, the point when its heat pulls you in and its symptoms, sore throat and headache and nausea, drift away. Laying on the couch, chills running down my back, I wiped the sweat off my forehead and stared into the abyss, searching for God on the ceiling. It was great.

In Teffi’s “Volya,” the Russian author describes воля, a state of mind that “takes no account of anything.” If freedom is a matter of law and an individual’s civil status, воля is “a feeling.” In the northern spring, when the sun’s pink light never leaves the sky, students run away from their dormitories, soldiers desert their posts, and sons abandon their families. They float through the forest, alone. If the authorities manage to track them down, they’re unable to explain any reason for what they’ve done.

Those who fall into воля live freer than free, their only company fern flowers and birds in heaven, their only conversation prayers with God at dawn.

Sickness is the last remnant of divine wrath, isolating us until, in its fever, we find faith again.